ANESVILLE, Wisconsin — Michael K. Fitzgerald suffered two painful shots to the body on Jan. 6, 2021, one of which still represents a serious threat to his life more than 45 months later.

The first shot struck him in the leg and neck at the U.S. Capitol — from explosive munitions fired and tossed into the crowd by Metropolitan Police Department officers. At the time, Fitzgerald was quietly capturing video at the police line on the West Plaza.

The second shot came more than 40 minutes later, just after he walked into the Capitol with a large group of protesters.

Something was very wrong inside, as he discovered during more than a half-hour in the restroom. He was bleeding. His undiscovered colon cancer was fully present, but it wouldn’t be diagnosed for nearly a year. By that time it was at stage IV and had spread.

Fitzgerald’s peaceful 39-minute visit inside the Capitol brought federal felony and misdemeanor charges. Despite occasional discussions with Fitzgerald’s attorney about dropping the case, prosecutors have refused to dismiss the charges, even though Fitzgerald’s doctor says his cancer is incurable.

“I know it’s all marching orders from the DOJ, which we all know are obviously conflicted and they’re politically biased,” Fitzgerald, 46, said during an interview at his home. “I just take some comfort in knowing that if Trump is re-elected, this will get straightened out.”

In September, Fitzgerald filed a status report with U.S. District Judge Paul Friedman in Washington, D.C., indicating that his recto-sigmoid cancer has spread to his liver. His treatment regimen would make it dangerous for him to fly to Washington for a trial.

“His cancer has an estimated prognosis from this date (Sept. 25, 2024) in overall survival of 12-24 months based on his current line of therapy and molecular features specific to his cancer type,” wrote Dr. Jeremy Kratz, Fitzgerald’s oncologist at the William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital in Madison.

Kratz said air travel and prolonged immobility would put Fitzgerald at increased risk of blood clots. His chemotherapy requires a 46-hour infusion of two anti-cancer drugs that put him at risk of local infection and require frequent follow-ups for IV fluid support and electrolyte replacement, the doctor wrote.

“It is anticipated that he will remain on chemotherapy and radiation for the remainder of his life based on his goals of pursuing life-prolonging therapy,” Kratz wrote.

Fitzgerald’s next court appearance is set for Nov. 8. He said he just wants the case to be finished so he can focus all of his energy on his wife and four children — and fighting the cancer doctors believe is related to his U.S. Marine Corps service.

“Why can’t they just leave me alone?” he asked.

Fitzgerald said even if prosecutors were to drop his case, he would still worry about it hanging over his head while he fights for his life.

“I don’t like the fact that if I ever were to beat cancer, those charges would be re-implemented and I would face maybe jail, prison time. So that’s a huge stressor. At the same time, with me being God-fearing, I’ve kind of let it go because there’s nothing I can do about it.

“I appreciate every day with my family a lot more, and I don’t take anything for granted. Both of them have kind of been a blessing in disguise in that regard.”

Gassed and shot

Fitzgerald was suddenly in a war zone. He had been quietly filming police and the crowd from the front row on the West Plaza beneath the inauguration stage at the Capitol.

Police had been firing and lobbing incendiary munitions into the crowd for nearly an hour, but Fitzgerald’s location was suddenly ground zero.

At 2:04 p.m., Metropolitan Police Department Sgt. Frank Edwards fired two 40mm shells over Fitzgerald’s head within less than 10 seconds, security and bodycam video showed.

Throughout the afternoon, Edwards stocked his orange munition launcher with 60-caliber hard rubber “stinger” balls and Skat Shells, which split into four fire-producing sub-munitions that release tear gas.

Another MPD officer was busy tossing incendiary grenades about 30 feet into the crowd. At 2:04:02 p.m., he lobbed one that landed just behind Fitzgerald. A blinding orange flash lit up the profiles of protesters at the police line, followed by a thud and a rapidly expanding cloud of tear gas.

Fitzgerald was looking right at the gas cloud as it flowed south at 20 mph to envelop the crowd at the police line. Within seconds, he doubled up and was incapacitated. He turned away and limped into the crowd. He dropped to his knees, fell on his face, and blacked out.

He’s not sure exactly when during the fusillade it happened, but one of the projectiles struck his neck. He said it felt like a baseball bat hit him. When he returned home, a deep bruise about the diameter of a tin of chewing tobacco formed on his neck. It took weeks to fade, he said.

Fitzgerald was sprawled face down on the concrete. The chemical delivered by many of the munitions on Jan. 6 was 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile — or Courson-Stoughton gas — a lachrymal agent that causes a burning sensation in the eyes, mouth, and throat, a tight chest, and difficulty breathing. The chemical munition typically incapacitates a person for up to 20 minutes. In people with compromised respiratory systems, it can be fatal, but most people recover after 10-15 minutes of fresh air.

Bystanders helped a dazed Fitzgerald to his feet, then used a jug of water to flush out his eyes. He said it felt like “military-grade tear gas.”

The crowd, he insists, had not tried to push through the police line, so the deployment of munitions made no sense to him. In fact, the exploding shells had the opposite effect from what they are designed for. They did not scatter the crowds but rather corralled them in tighter at the barricades.

“There was no reason for it,” he contends. “The crowd wasn’t getting unruly. The crowd hadn’t moved forward. There was no rioting."

“People were shaking hands with Capitol Police officers and saying, ‘Good job,’ and everything like that,” he said. “Then all of a sudden they just turned on us.”

Fitzgerald said he saw the munitions affecting people of all ages.

“I saw elderly people get hit, people in wheelchairs get hit, little kids get hit because they didn’t expect that,” he said. “They thought we were just there for a peaceful protest, and then all of a sudden they just started opening fire on people.”

The Metropolitan Police Department declared all of its uses of force on Jan. 6 “objectively reasonable,” including munition launchers, grenades, tear gas, pepper spray, and strikes with riot batons.

39 minutes in the Capitol

Fitzgerald entered the Capitol at 2:47 p.m., 35 minutes after the building was breached by the first rioters at the Senate Wing Door. He did nothing violent yet would be charged with violent entry and five other crimes.

The USA Today-owned Green Bay Press-Gazette seemed to suggest that Fitzgerald was guilty of the acts of those around him in the crowd. That is also the default belief of the U.S. Department of Justice about many J6 defendants.

“For about a minute and a half, rioters were seen on video ‘punching law enforcement officers, throwing objects at law enforcement officers and attempting to hit law enforcement officers with a flagpole,’” a Jan. 6, 2022, Press-Gazette story read.

Capitol Police security video, however, shows that Fitzgerald did none of those things. He was near the front of the crowd that pushed into the building, but he was filming the action and did not push against or strike anyone, video showed.

That mattered not one bit to the media, which adopted the DOJ’s narrative that Fitzgerald and thousands of others took part in an attack on democracy. They “stormed” the Capitol and attempted an “insurrection” at then-President Donald Trump’s specific direction, the narrative claimed.

“Apparently, he’s admitted to the FBI that he was there,” U.S. Magistrate Judge Stephen Crocker said during Fitzgerald’s first court hearing. “And maybe he got caught up in things. But he got caught up in what many people are characterizing as an insurrection, and people were killed.”

Prosecutors insisted that Fitzgerald wear a GPS ankle monitor, which Judge Crocker ordered over the objection of defense attorney Mark Eisenberg. After a few months, however, the monitor was removed.

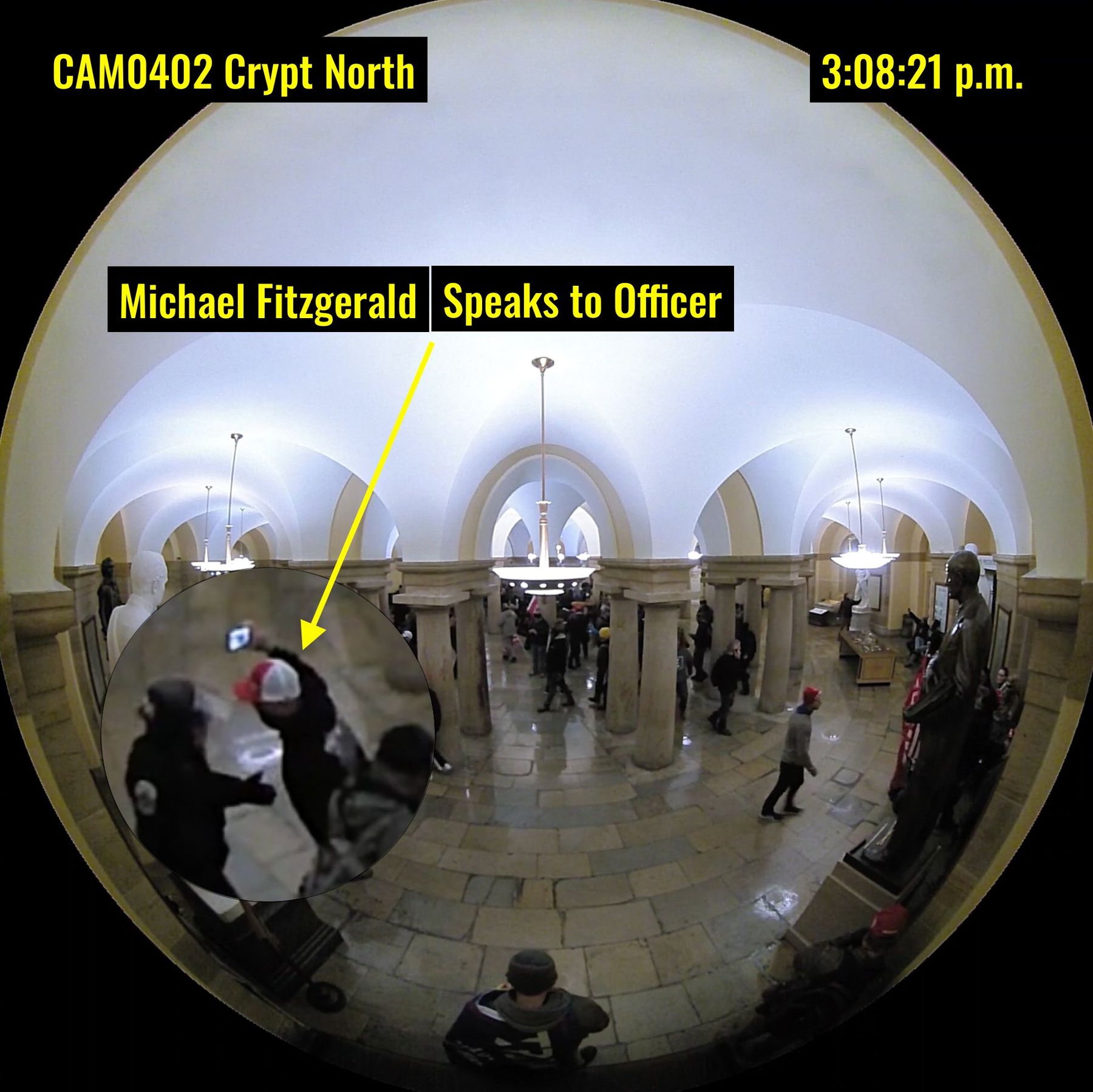

The story of Fitzgerald’s time inside the Capitol is told on Capitol Police CCTV and his own iPhone videos. He stayed in the Senate Wing lobby for a few minutes, then walked down to the Crypt. His main concern, he said, was finding a bathroom.

“All of a sudden people just started pushing,” he said. “I had one hand I’m trying to brace so I don’t fall down. I have my cell phone and I’m trying to record it, and we get pushed in.

“The first thing I did was to go up to the Capitol Police officer to say, ‘Hey, I got pushed in.’ He goes, ‘It doesn’t matter now.’ I said, ‘Can you tell me where the bathroom is?’ This is when the symptoms of my cancer were first starting and I was having a lot of issues.”

Fitzgerald’s wife called him while he was in the bathroom and told him someone had been shot at the Capitol. He had no idea that Ashli Babbitt had been fatally wounded three minutes before he entered the building.

“She told me not to go,” he said. “She said she had a bad feeling. I said, ‘What’s going on? Am I getting in trouble for being in the building?’ She said, ‘Do you not know what’s going on?’ I said no. She had to tell me.”

Fitzgerald retraced his steps to the Senate Wing Door and exited the building through a window. “I just left on my own,” he said. “Nobody told me to leave.”

On the way out, “I didn’t see anything,” Fitzgerald said. “I just saw it was still crowded, lots of people, and you could look down the street and it was nothing but heads. It was that packed.”

Most wanted man turns himself in

By the time Fitzgerald reached Reagan National Airport for a flight home late on Jan. 6, the newscasts were filled with dramatic, breathless reports of massive rioting and a “storming” of the Capitol. He couldn’t believe it. Aside from being knocked off his feet by tear gas and a munition shell, Fitzgerald said he didn’t see any large-scale violence.

“That’s when I started freaking out a little bit, but then I was thinking, ‘I didn’t do anything,’” he said. “I was a little bit comforted in that fact. When I got home, I called attorneys before the FBI even came and said, ‘What’s going to happen to me?’”

The first attorney who represented him did not view it as overly serious because he wasn’t violent and did not vandalize or steal anything or go into any Capitol offices, Fitzgerald said.

“He goes, ‘Well, this happens all the time. You’re just going to get a trespassing ticket and maybe a parading ticket. They’re not even misdemeanors; they’re just tickets,’” Fitzgerald said.

That prediction never came true.

Two FBI agents visited him on Jan. 9 after he called the Bureau to turn himself in. The FBI put out "most wanted" posters with a photo of Fitzgerald as No. 32. “I turned myself in because I figured that was the best way to go,” he said.

A month later, the situation took a big turn when 18 FBI agents raided his house, looking for the red Trump cap and custom sweatshirt he wore on Jan. 6. The entourage included an FBI SWAT team.

“They came rushing into my house with weapons,” he said. “You couldn’t move in here, that’s how many FBI agents were in my house. I turned around, and my whole yard is full of agents.

“I’m like, ‘All this for me?’ It was overkill,” he said. “I don’t know if they had a slow day or something. They were friendly, but they scared the crap out of my kids.”

Nothing else happened in the case until April 2021. Fitzgerald and his wife were in Illinois visiting a museum with their children when his cell phone rang. A federal grand jury had indicted him on two felonies and four misdemeanors.

“I honestly felt like I had a heart attack. It felt like someone just stabbed me right in the heart,” he said. “I couldn’t believe it. I’m like, ‘What did I do?’ I’m not naive. I know I broke the law by being inside, but I really didn’t think it was going to be anything more than trespassing.”

A grand jury issued an indictment on April 28 charging him with two felonies — civil disorder and obstruction of an official proceeding — and four misdemeanors related to entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds. At a May 7 arraignment hearing, he pleaded not guilty to all charges.

Prosecutors claim that while he was on the Upper West Terrace, Fitzgerald shouted to other protesters, “Go get their sticks,” referring to batons carried by police. On video from his own iPhone, however, his voice is clear: “They have sticks!” Fitzgerald shakes his head at the assertion. “They twist everything,” he said.

A superseding indictment was issued in December 2021, just before Fitzgerald got his cancer diagnosis. The indictment repeated the exact charges that were on the April 28 indictment. The only difference appeared to be that the U.S. attorney’s signature was now Matthew Graves instead of Channing Phillips.

Fitzgerald had been scheduled for court hearings in December 2021 and January 2022, but his life was about to get further toppled in a way that would push his case well into 2022 and 2023.

Fitzgerald said he visited the Veterans Affairs hospital in Madison complaining of blood in his stool — the symptom he first noticed in the bathroom at the Capitol on Jan. 6.

“I was freaking out and went up there three times telling them what was going on with my symptoms,” he said. “They kept turning me around and saying that it was just symptoms of hemorrhoids. I said, ‘That’s not true because I’ve never seen ounces of blood.’”

Fitzgerald decided to get a second opinion and scheduled an appointment at SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison for a colonoscopy. After learning that St. Mary’s doctors had ordered the diagnostic test, the VA relented and performed Fitzgerald’s colonoscopy.

“A couple days later I got a call saying that I had stage four colon cancer that metastasized to my liver,” he said. “At that point it wasn’t in my lungs. Now it’s in my lungs.”

After the first anniversary of Jan. 6 passed, Fitzgerald faced a brutal regimen of chemotherapy to shrink the colon mass and liver tumors. His Jan. 6 criminal case would have to wait — and wait.

“I was doing a really harsh chemo, to the point where I was bedridden six out of seven days, throwing up a lot, in the bathroom a lot,” he said. “They got my tumors down enough to where they could do surgery on my liver and in my colon.”

Initially Fitzgerald expected the surgery to be a minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure, but he was surprised at what he saw when he awoke from the anesthesia.

“I ended up waking up to my whole chest open with 54 staples and an ostomy bag,” he said. “So I was not expecting that. If you know anybody that’s ever had an ostomy bag, it’s not pleasant. I had it for 90 days, and if I would’ve had it any longer, I don’t think I would’ve been able to do it.

“So now I have a line from here all the way down under my belly,” he said. “Then it looks like I got a gunshot wound in my side from where the ostomy was. So I had to deal with that while dealing with the [Jan. 6] case.”

The DOJ did not respond to Blaze News' request for comment.

From the crucible to PTSD

Fitzgerald carries invisible wounds from his time in the U.S. Marine Corps. Based at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, Calif., Fitzgerald did tours in Kuwait, Korea, and Okinawa, Japan.

He still recalls the end of boot camp, when the recruits were put through a three-day test called “the crucible.” The final stretch was a climb up a steep hill they nicknamed “Mount Motherf***er.”

“So we get up there, and when we’re done, we’re at the end of the hills. That’s when we get our EGAs [Eagle, Globe and Anchor insignias]. They pinned them on our collars, and that’s when we sang ‘[God Bless the USA].’ We actually had Lee Greenwood there, so that was pretty special.”

It was his deployment to Okinawa that left him so scarred that he is now classified as 100% service-disabled. There were good things during his months on Okinawa. He got to climb the snow-capped Mount Fuji, Japan’s tallest mountain at 12,388 feet.

The nine-month tour got tedious, so Fitzgerald took college-credit courses and exercised a lot in his spare time. “One of the sayings was either become an alcoholic or a PT stud,” he said, noting that he pursued the physical training option over the booze.

It was a trip to the shooting range on Okinawa that forever changed his life and took the life of his friend Dan.

Dan had just gotten a “Dear John” letter from home and discovered that his wife was cheating on him. He was upset, so Fitzgerald gave him the best bit of tough-guy Marine advice he could muster: “I told him, ‘Stop being a bitch,’ basically. ‘I mean, there’s plenty of women out there who care. Move on.’”

The pair went to the base shooting range a short time later. Fitzgerald noticed that Dan was unusually quiet. Marines have to have their wits about them during practice and qualification, or they could find themselves in the line of fire. They’re never supposed to put themselves there on purpose.

“There’s a red line that you don’t cross, because then you’re in the direct sight or direct fire of everybody else,” Fitzgerald said. “He walked over that line and got lit up by three or four different Marines who were shooting downrange. He was killed instantly.”

The shock and horror of watching a buddy die in front of him didn’t hit Fitzgerald until he got home and finished his hitch in the Marine Corps. Suicide was not a stranger. Three men in Fitzgerald’s battalion took their own lives. But now it was intensely personal. The experience would shape Fitzgerald’s life for a decade — and not for the better.

“I wouldn't say I had PTSD right away,” Fitzgerald said. “I was just more in awe, I guess. Probably had a little bit of guilt. I don’t think it really hit me until I started getting in trouble.”

“I wrote some bad checks, got into drugs and girls too hard, and was on a mission of self-destruction,” he said.

That self-destructive mission over a 10-year period landed Fitzgerald in criminal court repeatedly for writing bad checks, using someone else’s identification, theft of movable property, criminal trespass to a dwelling, obstruction of police, and selling alcohol to a minor, court records show.

He said it all started when he used his mother’s car without permission and wrote some checks she gave him to pay bills. Fitzgerald said his stepfather insisted that he be prosecuted, while his mother did not want the police involved.

In 2013, the military classified Fitzgerald as fully service-disabled. The ruling and its basic income helped him steady his life.

Within a few years, he and his wife started a clothing business, selling custom T-shirts, caps, sweatshirts, and more to first responders, Second Amendment enthusiasts, and other conservative patrons. That led in 2018 to the founding of a charity to help homeless veterans by providing tiny homes.

All of that came crashing down after his arrest. It started with hateful messages on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. “People would call me traitor and piece of crap, piece of sh*t,” he said. “Pretty much all of the names you could get. They were like, ‘How could you serve your country and then commit treason?'”

Then the rage mob went after the family business, flooding Yelp and other ratings sites with fake negative reviews. “I went out of business with my apparel line because they would get everybody and their mother, 100 of their best friends, and they would leave all negative reviews saying, ‘I didn’t receive my stuff.’”

The hate campaign also caused donations to the charity to dry up, he said. “We lost all of that funding and donations from people because they would go on [social media] and just make stuff up on our Facebook page. They said, ‘Oh, this guy’s a J6er' or 'this guy is treasonous.’”

In the midst of it all, Fitzgerald lost his mother, Laurie Lynn Wallace, to a brain bleed and a stroke on Feb. 19, 2023. A 36-year head nurse at the Middleton VA Hospital where her son is being treated for cancer, Wallace, 66, came out of retirement to help out during the pandemic.

“We had our annual sleigh ride, and my mom starts slurring her words. My stepdad said, ‘What’s going on with you? You’re not making any sense,’” Fitzgerald said. “My mom was like, ‘What do you mean? You think I’m having a stroke?’” She then collapsed.

Despite emergency surgery at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Wallace could not be saved. “We had to let her go,” Fitzgerald said.

Laurie Wallace fled domestic abuse with her son, Michael, when he was little. Fitzgerald said his father was prone to violence.

“He threw a vase at my mom and missed my mom. It hit me and broke my collarbone. So my mom took me and never looked back.”

Take no days for granted

Through it all, Fitzgerald stays positive. His surgeries and cancer treatments have left him infertile. He continues to travel to the VA hospital for chemotherapy in the hopes of beating the cancer. He recently had an MRI to make sure the cancer had not spread to his brain.

“If I go up to the [Wisconsin] Dells and take the kids up there and I’m watching them at the water park, I’m like, ‘Is this the last time that we’re going to be able to do this as a family?’" he said.

“But then I’m thinking on the flip side — I could get in a car accident tomorrow and die. So I’m really putting everything in God, knowing that just because I have stage four cancer doesn't mean I couldn’t be here for another 10, 15 years.

“The way I’m looking at this is I need to make it in three-year increments,” Fitzgerald said. “Every three years there’s a chance of a new treatment or a cure. So if I can make it in those three-year increments, I’m doing good."

“I’m trying to stay positive because 50% of the battle is staying positive,” he said. “Obviously that helps your immune system too. I don’t take any day for granted. At first they gave me 24 months, and I’m past that now. So, I mean, that’s a good sign.”

In the nearly four years since Jan. 6, Fitzgerald has become an even bigger admirer of former President Trump, attending eight of his rallies. He worked as a Republican volunteer at various Trump campaign events.

He said he marvels at how Trump gave up a comfortable retirement to take on D.C. corruption and the ruling elites — all because the country was headed in a bad direction. He took a bullet and still stands strong.

“Everybody’s asking me why I support Trump,” Fitzgerald said. “He was a billionaire that didn’t need to do this. He was a Democrat and saw the light, became a Republican.”

Fitzgerald has seen a transformation in his wife, who was politically neutral before but is now a “full-blown Trump girl.”

“She’s been seeing with her own eyes and sees I like underdogs,” Fitzgerald said. “That’s another reason I love Trump, because the more that people hate him, the more that there’s something going on that people [on the left] are trying to cover up.

“That’s where I’m at,” Fitzgerald said. “He might be a billionaire, but he’s still the underdog.”

If you are a veteran in crisis or know someone at risk of suicide, call the Veterans Crisis Line 24 hours a day, seven days a week, by dialing 998 and pressing option 1.

Thank you Blaze Media for allowing us to share this article on our site.